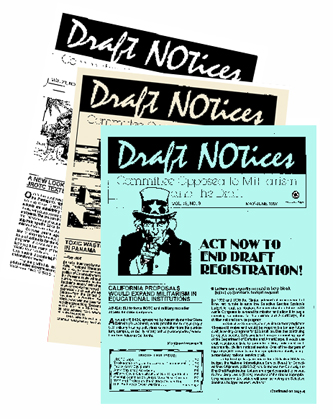

From Draft NOtices, January-March 2019

— Jesús D. Mendez Carbajal

Since at least the 1980s, Central Americans have been making the journey from their home countries, traveling through Mexico, many with the goal of entering the United States. Different waves of Central Americans have arrived in the U.S. because of various reasons including civil war, persecution, and violence. The shared reason among migrants for leaving their home behind is the constant instability in the region due in large part to the interventionist foreign policies of the U.S. Migrants are motivated, as well, by the drive to provide a better tomorrow for their children, families and themselves. Central Americans, like other immigrant groups in the country, currently hold varied immigration statuses, including U.S. Citizenship, Legal Permanent Resident Status, Temporary Protected Status (TPS), Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and undocumented status. This is to say that the experiences of Central Americans who reach the U.S. are also impacted by the legal status they hold.

Since at least the 1980s, Central Americans have been making the journey from their home countries, traveling through Mexico, many with the goal of entering the United States. Different waves of Central Americans have arrived in the U.S. because of various reasons including civil war, persecution, and violence. The shared reason among migrants for leaving their home behind is the constant instability in the region due in large part to the interventionist foreign policies of the U.S. Migrants are motivated, as well, by the drive to provide a better tomorrow for their children, families and themselves. Central Americans, like other immigrant groups in the country, currently hold varied immigration statuses, including U.S. Citizenship, Legal Permanent Resident Status, Temporary Protected Status (TPS), Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and undocumented status. This is to say that the experiences of Central Americans who reach the U.S. are also impacted by the legal status they hold.

In 2018, in comparison to past migration patterns, there was an astounding increase in Central American large group migration. The beginning half of the year saw the first large group of migrants including at least 300. This first group was made up mostly of Hondurans and arrived in Tijuana, Baja California, in April 2018 after starting their journey as part of the week-long Easter celebrations that take place across Latin America. This caravan was organized by Pueblo Sin Fronteras. According to their website, they are a group of volunteers dedicated to supporting vulnerable migrants and refugees in the United States and Mexico through “humanitarian aid and professional legal advice.” The migrants arriving in the U.S.-Mexico border region in the past year, specifically at the San Diego/Tijuana border port of entry, have shown up with determination to present their claims of asylum, a human right as dictated by the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights.

In response to the recent caravan and to the vast increase in asylum claims from Central Americans, as well as from migrants prior to the caravan and from other parts of the world, Trump and his administration have taken yet another opportunity to push anti-immigrant rhetoric and a flawed border agenda. In one outburst, Trump spoke about changing national immigration laws and the ways in which the U.S. carries out international mandates that require accepting asylum claims and giving everyone an opportunity to make and fight their case. Instead of upholding national and international standards, Trump, in his tweets and press conferences, has spewed abhorrent hate and exclusion toward those seeking asylum.

Read more ...

Since at least the 1980s, Central Americans have been making the journey from their home countries, traveling through Mexico, many with the goal of entering the United States. Different waves of Central Americans have arrived in the U.S. because of various reasons including civil war, persecution, and violence. The shared reason among migrants for leaving their home behind is the constant instability in the region due in large part to the interventionist foreign policies of the U.S. Migrants are motivated, as well, by the drive to provide a better tomorrow for their children, families and themselves. Central Americans, like other immigrant groups in the country, currently hold varied immigration statuses, including U.S. Citizenship, Legal Permanent Resident Status, Temporary Protected Status (TPS), Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and undocumented status. This is to say that the experiences of Central Americans who reach the U.S. are also impacted by the legal status they hold.

Since at least the 1980s, Central Americans have been making the journey from their home countries, traveling through Mexico, many with the goal of entering the United States. Different waves of Central Americans have arrived in the U.S. because of various reasons including civil war, persecution, and violence. The shared reason among migrants for leaving their home behind is the constant instability in the region due in large part to the interventionist foreign policies of the U.S. Migrants are motivated, as well, by the drive to provide a better tomorrow for their children, families and themselves. Central Americans, like other immigrant groups in the country, currently hold varied immigration statuses, including U.S. Citizenship, Legal Permanent Resident Status, Temporary Protected Status (TPS), Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and undocumented status. This is to say that the experiences of Central Americans who reach the U.S. are also impacted by the legal status they hold. On February 14, 2018, the unthinkable but all-too-common happened. A mass shooting occurred at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. Rumors about the identity of the shooter were that he was a former student who had been in JROTC. One week later, on Democracy Now, Amy Goodman's guest was Pat Elder, the director of the National Coalition to Protect Student Privacy. This organization works to counter the access that the military has to students in high schools. Mr. Elder went on to state that the shooter was trained in the marksmanship program at the same high school. On the day of the murders, the shooter wore his JROTC shirt. Also, among the killed were three JROTC students.

On February 14, 2018, the unthinkable but all-too-common happened. A mass shooting occurred at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. Rumors about the identity of the shooter were that he was a former student who had been in JROTC. One week later, on Democracy Now, Amy Goodman's guest was Pat Elder, the director of the National Coalition to Protect Student Privacy. This organization works to counter the access that the military has to students in high schools. Mr. Elder went on to state that the shooter was trained in the marksmanship program at the same high school. On the day of the murders, the shooter wore his JROTC shirt. Also, among the killed were three JROTC students.